Running a full animatronic network over consumer hardware is a fun challenge! 😅

Motion Data

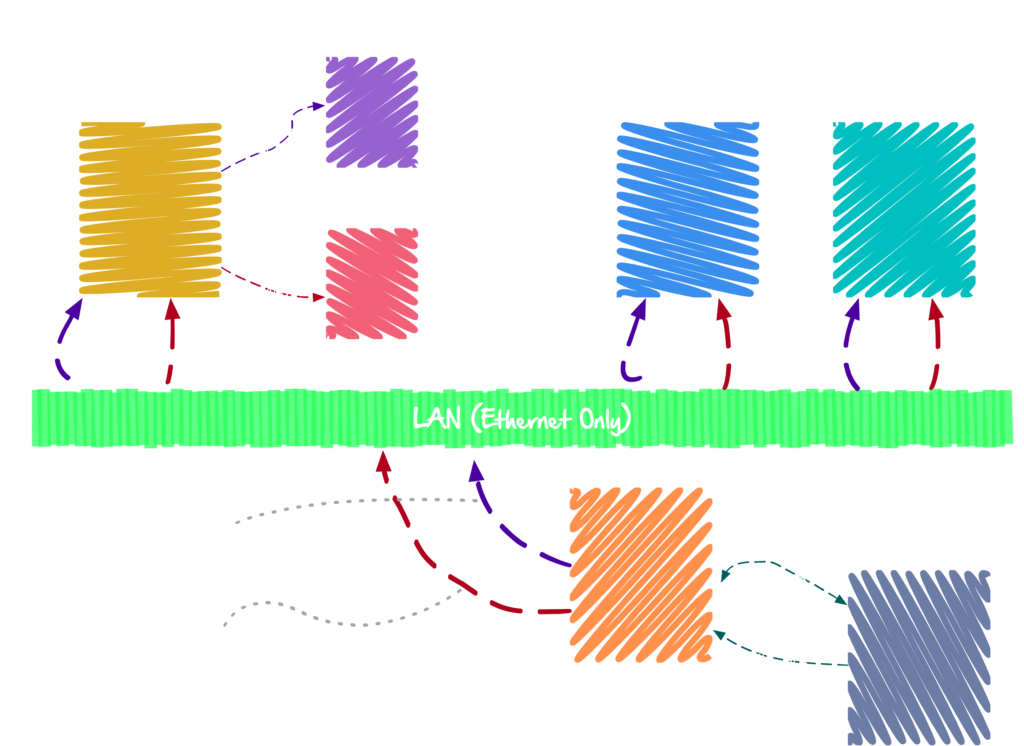

The first version of my animatronic network was based on DMX-over-RS485. (Yes, the lighting protocol.) The current version is based on DMX-over-IP, also known as e1.31. Traditional DMX still works fine, but it requires an e1.31 to DMX bridge, such as OpenLighting.

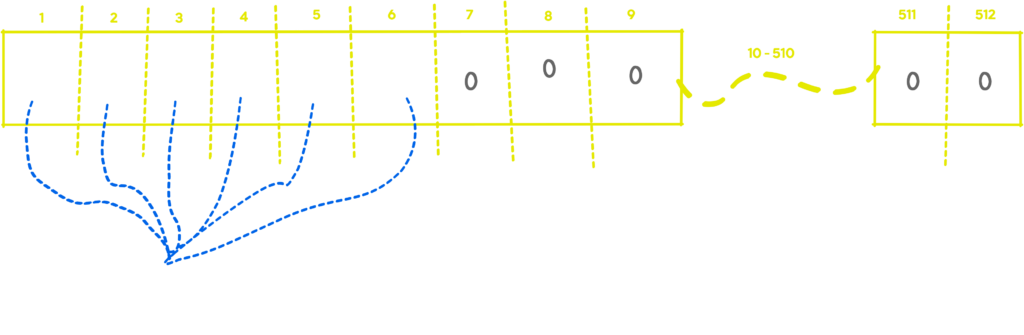

DMX has 512 8-bit channels, and usually runs around 50Hz. This aligns very nicely with how hobby servos work. The server sends out a steady stream of e1.31 frames over multicast UDP at 50Hz, designating the desired set of positions of all motors on the network. (50Hz means each frame is 20ms.)

Each creature has an offset into the array of where its motor positions start. When an e1.31 frame is received by the controller it looks for its initial offset, and then sets its servos to match. It repeats this process for every frame of motion data it receives.

I chose DMX / e1.31 because it’s very well supported. There’s lots of tools to debug it, lots of libraries know what to do with it, and I can use non-animatronic fixtures on the network. (For example, if I wanted to include lighting cues in an animation, I could.) Choosing DMX was one of the best decisions I made in this process. It has worked out extremely well!

I have not removed DMX over RS-485 support from my code. If I was in a challenging RF environment where Ethernet would not work (highly unlikely!), I could still go string DMX cables around between creatures and keep on going.

Audio Data

Audio data is transmitted around the network as Opus encoded multicast RTP packets.

There are 17 channels in use total. Channels 1-16 are for each creature (I do not have 16 yet, but I have visions of getting there!), and channel 17 is for background music.

The server will broadcast out all 17 channels at once, each one on a different multicast address. Each creature controller will listen to the RTP stream for its own creature plus channel 17 for background music. It mixes the two together and ships it off to the attached audio device, which converts it to analog audio that’s broadcast by a speaker.

Each creature has an audio channel defined in its creature definition. The controller uses this data to know which channel to listen to, and the server uses it when creating dialog for ad-hoc animations.

The result is really cool. Audio streams with virtually no perceivable lag around the stage, and the dialog for each creature appears to originate from itself.

Creature Console

The Creature Console uses more traditional methods of communication. It uses a REST API for most interactions, and establishes a WebSocket for real time updates.

The WebSocket is bidirectional. The server broadcasts out events, and the client will send motion data when an animation is being recorded, or a creature is being controlled live by a human.

The system is able to function autonomously without a connection from a console, and running autonomously is the normal mode of operation.